JULY 26, 2023

Art review: Animal magnetism

The group exhibit “Biomass,” in a Pearl District warehouse space, reunites a contemporary art community after a lengthy pause.The group exhibit “Biomass,” in a Pearl District warehouse space, reunites a contemporary art community after a lengthy pause.

By BRIAN LIBBY

Wendy Given’s radiating, hanging sculpture; Renée Zangara’s triptych “Revelation”; Crystal Schenk & Shelby Davis’s black tiger sculpture in “Biomass.” Photo: Jeff Jahn

Before I even entered the exhibit space for the group art show “Biomass,” at the circa-1906 Maddox Building in the Northwest 13th Avenue Historic District, the past seemed to come to life.

Curator Jeff Jahn cautioned that, because I was wearing flipflops on this hot July day, I should beware of nails protruding from the exhibit floor. “We’re calling this space The Oyster,” he joked, as if to acknowledge a rawer, early-Pearl District warehouse vibe.

The Maddox — originally known as the Prael, Hegele Building and home to a glass and crockery manufacturer — certainly looked the part, with its exposed rafters and voluminous square footage. The building also comes with its own art-past: Blue Sky Gallery was for many years located within its walls. What’s more, one block south is the Pearl Building, where the pioneering Jamison Thomas Gallery was located; gallerist William Jamison coined the term “Pearl District.”

The neighborhood as an arts destination began right here. The Maddox Building’s owner, Al Solheim, who made the ground-floor space available to Jahn for “Biomass,” is even sometimes called the father of the Pearl District, having been among the first to have redeveloped heretofore-industrial enclaves into condos some four decades ago.

Works by Eva Lake (left) and Kendra Larson in “Biomass.” Photos: Brian Libby

Over the ensuing four decades, the Pearl has retained its identity as a visual arts Mecca, with today just over half of the Portland Art Dealers Association member galleries locating within the district. Yet the district’s popularity might seem to have peaked: First Thursdays, which used to bring large crowds here one evening a month for evening exhibit openings, are not such an event anymore, which was arguably true even before the pandemic. And the Pearl District’s artistic center of gravity has moved east, around the North Park Blocks.

If the location evoked the Pearl’s beginnings, the show was refreshing in another way: Jahn and this community of contemporary artists coming together again after a few years’ absence. “Biomass,” on view through August 27 (but open only 12:30-5 p.m. Saturdays plus 5:30-8 p.m. Aug. 3 for the First Thursday artwalk), bills itself as the first large-scale art warehouse exhibition since before Covid began. Jahn, a nearly ubiquitous presence in the city’s visual art scene for more than two decades, as a critic via the PORT blog and as curator of several group shows, had not put together an exhibit or written a review in some three years. And the “Biomass” roster features more than 30 local and regional artists who have together weathered the past half-decade’s storm.

A Tia Factor painting brings a web of brightness. Photo: Brian Libby

Beyond that theme, many of the chosen artists seemed to share work they had created during Covid lockdowns, without the usual necessary consideration of how it would fare in the market. At a July 22 talk featuring three “Biomass” artists, for example, Morgan Buck discussed his airbrush painting “Cats in the Bag,” which is just that. If the subject matter seemed meant for a Hallmark card or Internet meme, Buck nevertheless spoke sincerely of finding the right flat-black background from which these feline eyes, isolated against it, could stare out from the sack they’d climbed into. As if to tip the scale into silliness, Buck took the extra step of adding a Garfield figure to the foreground. In an odd way, my favorite moment that afternoon was when Buck momentarily struggled to remember the fictional name of Garfield’s owner, and the assembled audience, like some pop-cultural Greek chorus, answered in unison: “Jon!” Sean Healy’s drawings “Egg’s Nest” and “Dionysus.” Photo: Brian Libby If classic Generation-X irony was on display, so too was its opposite. Buck was followed by artist Sean Healy, who explained that his two “Biomass” pieces were prompted by a personal milestone. Fighting back tears, Healy, an adoptee back in 1971, told of finding his birth parents during the pandemic, including his father, a former security man for the Hell’s Angels. The artist, who most recently has worked in sculpture, also spoke of returning to an artistic first love: representational drawing. Hence his two contributed pieces, part of an upcoming solo show this fall at Elizabeth Leach Gallery: drawings of a nest (“Eggs Nest”) and of a primate (“Dionysus”). There was no mistaking that Healy had been inspired by finding where he came from, and thinking about what it means to be a human animal.Renée Zangara’s triptych “Revelation.” Photo: Brian Libby

Entering the exhibit, straight ahead in the middle are three relatively large-scale works anchoring the 3,000-square-foot, double-height space. Most prominent, almost like a disco ball for the exhibit, is a hanging sculpture by Wendy Given called “Cauda Pavonis” (translated as “tail of the peacock,” a reference to alchemy) with feathers radiating out from a dark orb. Next to it is a floor-mounted black tiger sculpture by Crystal Schenk & Shelby Davis. Then there’s a multifaceted piece by Renée Zangara called “Revelation.” On its front is a triptych painting and drawing hanging curtain- or clothing-like from a steel frame, and a small sculptural installation is on the other side, taking advantage of the white backside of the canvass. Zangara, the third and final artist speaking about her work, first acted as a kind of cartographical tour guide, pointing out a combination of landscape and map-like elements including a wetlands, railroad tracks, and her own house. By combining drawing and colorful paints, Zangara rendered not just a kind of double-exposure but also a sense of erasure and re-making, like the Impressionist painter-protagonist in Emile Zola’s 1886 novel The Masterpiece, repeatedly painting over what he’d done. Only in Zangara’s work, the intent was deliberate, creating a work that felt both primal and playful, not unlike the collective identity of the show. (A second artists’ talk, featuring Eva Lake, Epiphany Couch and Kendra Larson, is scheduled for 3 p.m. Saturday, July 29.) An Erik Geschke sculpture. Photo: Brian Libby Of course, with a group show of this size and especially given its theme, touring “Biomass” is not about individual works so much as an ecosystem, in this case featuring mostly established mid-career artists and a few emerging voices, and a mix of media. In many cases, there were natural pairings. Near the entry door, for example, are two depictions of passages, with entirely different tones. A Corey Arnold photograph of a bear emerging nocturnally from a decaying house’s basement, “House Bear,” faces an Eva Lake collage, “The Torso No. 10,” with a headless woman’s torso coming out of a curvy antique Egyptian vase. Primal freedom meets cultured oppression. Around the corner, the V. Maldonado painting “Sister Earth Shares Her Secrets: Owl Encounter,” striking in its monochromatic sweet-spot between representational imagery and abstract pattern-making, hangs frameless from the wall just below Kendra Larson’s “Owl” sculpture, and next to two Matthew Dennison drawings to the left, one called “Each Bird Knew,” and to the right a tiny Brian Borrello neon sculpture called “Consumer Capture,” which spells out in all caps, “EAT,” and which is attached to an animal trap.A Gabriel Liston painting pops out against the white brick wall. Photo: Brian Libby

Across the room, Buck’s cat-eyes painting hangs next to two mixed-media works by Laura Fritz, each a sculpture in simple black geometry (a rectangular block, an obelisk) with a video-based projection of moving animal silhouettes: an older piece featuring a cat (“Transposition”) and a newer piece featuring bees fighting off hive collapse syndrome (“Alvarium 3”). Other captivating moments came from juxtapositions. So many works were in black and white that pieces with color stood out, be they the Erik Geschke sculptures “Vanitas” and “Cleaved,” the Jeremy LeGrand hanging sculpture “a new landscape’s skin” beside it, the Gabriel Liston painting “When the season’s over,” or the two Tia Factor paintings “Sun Web” and “Web Rising.”Works by Buck Corvidae-Schulte (left) and Sandy Roumagaux represent a younger and older generation of artists, respectively. Photos: Brian Libby

While Generation X may have been the best represented, there were also younger (the youngest being Buck Corvidae-Schulte) and older artists (like Newport painter and former mayor Sandy Roumagoux), too. And there were juxtapositions of time, with many artists pairing one older and one newer work. In an email this week, Jahn called “Biomass” both a class reunion and a survivor’s show. While both labels apply, maybe given the exhibit’s theme, the latter is more appropriate. It’s not to say “Biomass” evokes a cold Darwinian calculus, but rather a celebration: of having hacked our way through the thickets into a clearing of sorts, pausing momentarily to drink from the spring and take in the view. *** “Biomass” is on view through August 27 at the Maddox Building, 1231 N.W. Hoyt St. Hours are 12:30-5 p.m. Saturdays only, plus 5:30-8 p.m. Aug. 3 for Portland’s First Thursday gallery walk.Inscribed on the shaft of a gold-bladed scythe mounted on the wall, Given’s words place this simultaneous symbol of death and fruitful harvest within a context of re-engagement with humanity’s oldest intuitions. Similar themes of mortality and immortality haunt this darkly lyrical exhibition, both re-evoked and reversed reverently and/or irreverently to suit the circumstances of a time in which nature and the symbols it suggests have been altered by a fast-changing physical and spiritual climate.

Given, a one-time Atlanta resident now living in Portland, Oregon, has exhibited her work alongside Portland artist Ryan Pierce’s in a previous exhibition that made clear how well their independently conceived artistic projects mesh. In this show, it is occasionally difficult to be sure which artist created certain works, even though their primary styles are immediately recognizable.

In general, Given’s lyricism is less ironic than Pierce’s, but is frequently unnerving nonetheless. As the appropriated scythe might indicate, growth and decay and the resulting folkloric offshoots are often on Given’s mind. A Death’s Head Beetle is displayed in a French pocket-watch case, as though it were the relic of some barely imaginable saint. Jewel-toned beetles swarm over bunches of grapes in an adjacent color photograph. Actual taxidermied beetles crawl between matching clay sculptures of an outstretched white snake holding a feather in its mouth and a lustrously black snake coiled protectively around gold-covered porcelain teeth. These creatures are the attendants of a small “Wild Woman” figure composed, memorably, of wood, feathers, pussy willows, glass, bone, rabbit fur and crystal.

The sense of mythic archetypes run pleasurably amuck is extended by the presence of a taxidermied white peacock, its tail composed of fronds and other plant matter, with a small white mouse clinging attractively to its neck. This atmosphere of mysteries lost and recovered extends outward to the cosmos in “Starshine,” an eight-sided floor sculpture of mirrored triangles that alludes to the dispersion of starlight. It extends inward in a triptych of photographs in which two nightscapes featuring the light reflected from the retinas of animals flank a similarly dark central photograph of the tree-branch-like blood vessels of Given’s own retina.

Given’s lushly excessive and playfully uncanny body of work is complemented by Pierce’s sculpture and paintings, which represent nature overwhelming culture’s ruins after a climate-change apocalypse. “Terminal Degree” depicts a raven using a stick to create a drawing on the cracked glass of an empty picture frame that is half-obscured by the sprawling black hollyhocks that are the subject of the corvid’s artwork. The mysteriously titled “Mask for Night Farming” portrays the foliage of a sweet potato vine overrunning the fragments of a broken piece of ceramicware decorated with the representation of a snake not unlike the clay serpents that coil throughout Given’s segment of the exhibition.

“Invasives #5” is one of a series of hollow stoneware conquistador portrait heads that Pierce inverts for use as a vase for floral arrangements that decay over the course of an exhibition. It is a witty collision of nature and history in which both opponents appear to be the losers, just as the plants and animals in the paintings appear to have triumphed only uncertainly and uncomfortably over human artifacts in a habitat that no longer forms much of a home.

Given, on the other hand, remains hopeful in the midst of her often macabre symbols set amid surrounding darkness. “Paradis,” a large mixed media painting on paper, is the most multilayered emblem of this: a richly colored representation of an anatomical photograph’s cross section of a human torso, the strangely abstract shape is displayed against a solidly black background in a manner that suggests that the human body is itself a paradise, an English word derived from the Persian for “enclosed garden.” In Given’s symbolic universe, and to some extent in Pierce’s, the insistent materiality of nature opens out ultimately into mysticism.

January 28, 2016

Wendy Given and Ryan Pierce: mysteries in the wilderness

By GRACE KOOK-ANDERSON

The idea for Eyeshine came together as Given and Pierce hosted this past summer’s Signal Fire Outpost Residency—an intensive residency program set on public land. Their discussions, usually at night after full and active days, wandered around such topics as wilderness, animal and plant imagery, nocturnal life, and the embodiment of mysticism.

Three of Pierce’s paintings in the exhibition are outdoor still lifes. Their suggestion of beauty is entangled with the threat to the landscape—natural, invasive, and manmade objects, side by side. Using flashe acrylic and spray paint, the paintings’ flat quality emerges. Even the light source appears harsh, as if under direct noon light, unforgivingly exposing all surfaces.

Pierce’s sculptural works focus on the image of the conquistador—an antagonist recently a focus in the artist’s body of work—with haunting mask-like faces. Invasive #7 is installed like a museum collection of culled objects from deep under sea. The metallic glaze outlining the marks of where they have broken or cracked emphasizes their museological preciousness. Just like the tradition of kintsugi—the Japanese art of showing the object’s history of breakage and repair—the breaks in Invasive #7 seem to symbolize broken marks upon the lands the conquistadors encountered, marks of colonization, still evident today.

As Pierce touches on the Age of Discovery as a parable for our contemporary moment, Given also looks to the past in this exhibition—the Romantic era touching upon nature with a gothic mood—oval shaped photographs, nocturnal sightings, imagery of crows, and peacock feathers. Unlike Pierce’s brightly lit subjects and artifacts crushed by time, Given’s sculptures and photographs emphasize the night, shadows, reflections, and the ethereal realm of alchemy.

The most striking visual element in the exhibition is Given’s hanging sculpture Cauda Pavonis, made of long peacock tail feathers with the eye of the feathers radiating out, hanging from the ceiling. The blackened feathers create a soft, yet dramatic silhouette. Their original bright colors are subdued in blackness, but with slow movement from a breeze, subtle shifts of color can be seen. In the alchemic term, the cauda pavonis (peacock tail) is when an array of colors appears through various stages of transformation. Given begins with blackening—a decomposition in alchemy—but the inherent colors of the feathers remain evident. Their transformative colors endure.

Given’s three photographs set in individual oval frames with a convex Plexi-mount give the illusion of eyes. In these landscapes, wiry branches appear like retinal blood vessels. Similar to the eye imagery in the peacock feathers in Cauda Pavonis, these photographs emphasize the presence of the eye, not only as a physical presence in the space, but underlining moments of inwardness from viewers. Similarly, Starshine is a mirrored octahedron reflecting the interior space of the gallery and the people who walk nearby, slightly altering our visual cue of space, and ultimately directing the viewer inward.

Though the approaches in the practices of Given and Pierce are rather different, Eyeshine creates an engaged conversation between works and subjects, with space to breathe and reflect upon shared ideas.

Eyeshine is the first in a series of exhibitions Pierce and Given will work together on. Eyeshine closes Friday, January 29. Their next exhibition, titled Nocturne, is scheduled to open at whitespace in Atlanta, Georgia, on April 1, 2016.

Do you recall the apple that your middle-school art teacher forced you to draw with painstaking detail. Maybe you think of flower-filled paintings hanging in hotels or of gallery paintings that you rush past to get to the landscapes and portraits.

If this is your perception of still life, then the Hallie Ford Museum of Art’s new exhibition, “Stilleven: Contemporary Still Life,” will blow your mind.

Decaying fruit, a mysterious crime scene, plastic that won’t biodegrade, suspended animal skeletons, Middle Eastern politics and optical illusions — “Stilleven” has them all. The exhibition includes more than 60 works by 27 Northwest artists. More than paintings and drawings, the exhibit features a variety of media including photography, sculpture, fiber art and blown glass.

John Olbrantz, the museum’s director, organized the exhibition with Jonathan Bucci, collection curator. “Stilleven” is Dutch for “still life” and is pronounced “sti-LAY-ven,” Olbrantz said. While still life has origins in antiquity, the genre reached its pinnacle in the work of the 17th century’s Dutch and Flemish painters.

“Still life is an observation of an arrangement of objects,” Olbrantz said. “It’s a careful study of those objects. That’s the traditional definition of still life, but our exhibition takes that traditional notion and blows it up and says, ‘Yes, it can be this, but it can also be much more.’”

Here are a few ways “Stilleven” is much more.

Trick the eye

When you first look at Katherine Ace’s pieces “News with Words” and “Once Upon a Time,” they look like traditional still-life paintings of fruit sitting on newspapers. Moving in for a closer look, you realize the newspapers are actually collages created from newsprint clippings. Because Ace placed the print scraps so meticulously, your eyes are tricked into seeing a painting.

Ace’s work builds upon the tradition of 19th century American “trompe l’oeil” artists. The term is French meaning “to trick or fool the eye,” Olbrantz said.

Margie Livingston’s sculpture “Block of Blocks with White Pour, Large” is a “trompe l’oeil” that challenges traditional notions of still life. Observing the sculpture, Bucci said, “It looks like a stack of books or a block of tiles and then you realize that it’s actually paint.”

Who would have imagined that slices of dried paint could look like beautiful veins of marble?

Beauty in the mundane

Another tradition within still life is seeking beauty in mundane objects. A series of photographs by Holly Andres finds beauty in the backseat of cars. In “Backseat Vanitas (Suitcase),” she transformed the scattered contents of an open suitcase — pearls, makeup, lingerie and loose change — on a beige leather seat into a fantastic study of color and light.

The photograph also tells a story. What happened in the backseat of this car? Love or violence? A closer observation reveals a few fragments of shattered window glass. The mystery deepens. Even mundane objects have a complex story to tell.

Karen Hackenberg’s painting “Amphorae ca. 2010” features water bottles. The bottles, in all their glory, are spellbinding and beautiful. They also make a statement.

Political relevance

Hakenberg takes plastic objects that she finds on the shore of the Olympic Peninsula and arranges them against the breathtaking landscape in which she found them. The resulting juxtaposition raise questions about the environment and pollution. Just around the corner of the museum, Amjad Faur’s black-and-white photographs challenge the political happenings in the Middle East.

Bucci said, “The way artists are making still life relevant is by looking at relevant issues and using still life to address those contemporary issues.”

Enormous fruit and skeletons

Another way some of the exhibited artists challenge the traditional notion of still life is with the huge scale of their art. A centerpiece of the exhibition is a giant 3-D bowl of glass-blown fruit titled “Still Life.” Artists Joey Kirkpatrick and Flora Mace’s oversized fruit is a whimsical play on the use of fruit in traditional still life.

Henk Pander’s painting “Flight” is nearly 7 by 12 feet. Olbrantz said, “How many people think of still life on that scale?”

Pander, who grew up in the Netherlands during World War II, came out of the still-life tradition. After moving to Portland in the 1960s, the violence and enormity of the American landscape influenced his art. He collects animal bones and other items that he finds in the desert and builds huge installations that he paints. “Because of the scale, nature and drama of it, it extends the still life into a more contemporary way of looking at it,” Pander said. “Flight” features a reanimated horse skeleton that Pander suspended from the ceiling. “It’s about war, death, biology, still-life painting, somewhat reflective of the time we live in ... and the great die back of animals in the world.”

Forbidden fruit

Pander’s work builds upon the vanitas — Latin for vanity — paintings from the 16th and 17th centuries. This genre “deals with the passage of time, and that all comes to an end,” Pander said.

Wendy Given’s photographic series of “forbidden fruits,” one of which features beetles climbing on green and black grapes, also builds upon the vanitas tradition. “Influenced by creation mythologies of varying international cultures,” Given said, “the photographs recall the inescapable reminder and lore of mortality and the brevity of our fleeting pleasures.”

Why attend?

If you’re looking for a great introduction to the art of the Northwest, Olbrantz encourages you to attend “Stilleven: Contemporary Still Life,” which is on exhibit through Dec. 20.

“All contemporary art exhibits can be beneficial to the viewer. It is a way to check the pulse on our society and gauge current cultural concerns,” Given said.

The imaginative, relevant and experimental collection will stretch your understanding of still life. You may even reconsider the relevance of that middle school art lesson.

<<FULL ARTICLE>>

July 21, 2015

Wendy Given speaks at PNCA

By Jeff Jahn

<<FULL ARTICLE>>

March 14, 2014

Fan Mail: Wendy Given

By A. Will Brown

Mythos: fantasy, fiction, legend, saga, parable, fable, narrative, invention, fabrication, yarn. The conceptual distance between myth and the concrete manifestations of mythology is a potentially endless—yet meaningfully orderable—list of synonyms. But with each word the gap shrinks, as mental images of processes and then objects emerge, even if just as puns. Wendy Given is bridging the gaps between the abstract idea of a mythos and its textural and visual components—the story.

<<FULL ARTICLE>>

October 10, 2013

Getting metaphysical at Whitespace

By Jay Bowman

There is a separate and distinct theme which contributes to the witchcraft response: that of alchemy. The embrace of mythology, ritual and spirituality separates alchemy from modern science and those concepts are precisely what is present in Given’s work. A profile picture of a rabbit on a plain white background instead of its environment next to a mushroom on an equally plain black background. They comes across equal parts clinical and mythological: it not only appears to be a scientific study, but also, ingredients to a potion.

<<FULL ARTICLE>>

September 24, 2013

Review: Wendy Given’s uncertain identity, Martha Whittington’s canaries in a coal mine

By Jerry Cullum

Given’s photo exhibition, “Claw Shine Gloam & Vesper,” bears a less than obvious title. It begins with a word that alludes to animal existence and moves on to conditions of light and time of day, using archaic words for the evening star and the moments of transition between dark and light.

The title of the still-life photo “The Hour Between Dog and Wolf” offers a further clue that moments of frighteningly uncertain identity form a major part of Given’s interests and intentions. In this case, a candle and two coyote skulls suggest an updating of 17th-century Dutch vanitas paintings, a theme repeated throughout Given’s newest body of work.

<<FULL ARTICLE>>

May 5, 2013

Interview

Are your pictures closer to documents or myths?

My pictures are a type of becoming—past and future combined, both chronicle and tradition. What has happened and what can be. Photography is quite mythical, and always has been so. All picture production has potential to be perfidious and misleading. I do not produce pictures to communicate a specific thread of verity or to try to trick the viewer. I construct images to shift and open thoughts, to alter and propagate potential belief.

Do you believe in the iconography that your photographs represent and deal with?

I do have a cat, yet, my cat is not black.

Are you exploring your relationship to nature or mankind’s relationship to nature?

Nature, in my work, is a foundation of power, irrefutable and mystifying, both intelligible and arcane. I think animals, rocks, and plants hold keys to the known, the unknown and the essential. They are the true ancients and hold innate unspoken cues—cues that inform the way I believe that art can ultimately function effectively. It is a yearning to tap into awareness, an unspoken understanding that we are all and always will be (as humans) a very important part of nature. A call to be cognizant, to be present.

Your photographs are based in stories, folklore and mythology, can you talk about how they are translated into reality? Are they real to you?

Folklore and mythology translate through the lens of my images via constructed visual abstraction—truth with a honed bend. Reality is changeable, malleable—the eternal morph. The only reality I can possibly know is time and gravity. All else is ebb and flow, wonder and dark matter.

What experience do you want the viewer to have with your work?

I want the work to occupy a place or feeling of familiarity with the viewer, it can be unsettling and at the same time comforting, a humorous position and intense recognition or premonition.

Ask yourself a question and respond.

What is of relevance in this life, this place I exist?

It is vital for me to remember to look up and to listen carefully to the natural sounds enveloping me, acknowledge all the sentient souls, what is familiar—familial. I will follow the animal tracks. I am trying to pinpoint what scares me most when I am alone in the woods or swimming by myself in the ocean. This is relevant to me, this can and should be my reality.

January 17, 2013

New Art Photography:

Wendy Given’s Spiritual Mythologies

By Jon Feinstein

Each photograph begins with the selection of a single word or phrase that is tied to mythology, and often becomes the title of the piece. She pulls from traditions of folklore ranging from Scandinavia, Africa, Germany, and The Netherlands, among others, and is fascinated by their tendency to overlap. In order to stage the shoot, Given researches historical texts, folklore and imagery related to the origins of the word and then plans, scouts, collects costumes, and props. While many of these photographs are elaborately staged, they transcend the contrivances of Gregory Crewdson- and Jeff Wall-derived early art school imagery in exchange for playful, genre-defying tropes.

Given’s work is not merely a reference point to old tales, but a living mythology that she describes as “integral to the comprehension, reverence and preservation of nature as a whole.” It’s about an ongoing quest to understand the spiritual relationship between humanity and the natural world. Every object, living or not, appears to breathe and pulse, to have a soul when it confronts her lens. A spider web has the same significance as a purple Martian rock, and a dimly lit, grainy photograph of a witch has the same tension as an overturned canoe. This fluid connection between aesthetically disparate images is what makes them so successful. It allows viewers to approach the images from different perspectives and ultimately come away with a uniquely spiritual experience.

December 31, 2012

Looking back at 2012: best and worst

So who were the breakout artists this year?:

<<FULL ARTICLE>>

December 29, 2012

Once Upon a Time,

200 Years Later, in Pictures

This month marks the bicentennial of the publication of Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm’s “Kinder-und Hausmärchen” — “Children’s and Household Tales,” in English, but more commonly known as Grimms’ Fairy Tales. The collection of stories — “Sleeping Beauty,” “Little Red Riding Hood” and “Rumpelstiltskin” are just a few of the most well known — have been revised, retold, reinterpreted and even Disneyfied so many times over the past two centuries that it’s easy to forget the original tales were a potent mix of the macabre, fantastical and downright creepy.

<<FULL ARTICLE>>

Feb 19, 2011

Book Marked

I find Wendy’s work to be both funny and terrifying. Like Adam Eckberg, Wendy Given creates staged scenarios, but are much more narrative driven. While Adam’s work pays specific attention to the phenomena of light and color, Wendy’s staged work deals more with fairytales and cultural tableaux. I think what attracts me most to her work is its ability to take a genre that’s been done to death in art school, and give it a fresh life.

<<FULL ARTICLE>>

Wendy Given re-reads magic

and modernism at Whitespace

By Jerry Cullum

There is reason to note that many of the works in Wendy Given’s Turn Your Back to the Forest, Your Front to Me at Whitespace made their debut a few months earlier in a show titled How to Explain Magic to a Dead Rabbit at this ex-Atlanta artist’s Portland gallery. The title of that exhibition, an allusion to Joseph Beuys’s famed performance How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare, indicates Given’s debt to mystical modernism.

<<FULL ARTICLE>

Review: Wendy Given’s dark

and beguiling fairy tales at Whitespace

By Felicia Feaster

Sometimes art is simply an object on a wall, beguiling for its aesthetic or intellectual properties but undeniably inert and aloof. And some work has the immersive properties of moviemaking: you enter willingly into the world the artist has conjured up, eager to be enchanted. Wendy Given’s solo exhibition at Whitespace gallery, “Turn Your Back to the Forest, Your Front to Me,” through February 26, fits into the latter category.

<<FULL ARTICLE>>

June 2009

Diem Chau and Wendy Given

at Fifth Floor Gallery

Given's grouping of photographs commands the most serious attention because of its isolation on the spare upper floor of the gallery. Her C-print photographs on Plexiglas feature carefully lit peanuts against smooth black back-grounds. As a child, Given's family taught her a game-passed through generations of the artist's family in the Netherlands-that involved searching for images of elves inside peanuts. The carved peanuts in Given's photographs enlarge the "elves" to approximately thirty times their actual size, revealing a tiny world hidden in plain sight. Peanut Elf, fig. 2 (2008) stares at viewers from under a floppy hat with a clever wink, and Given utilizes the bud of the peanut to create the elfs beard. It's an incredible transformation. The dramatically lit carved orifices of the elf's face seem to take on a monumental quality while shadows exaggerate the form. Peanut Elf, fig. 9 (2008) depicts a gamine elf in profile, his delicately pointed earlobe turned toward the camera.

The peanut elves have a wondrous quality, not in that they are carved with particular accuracy, but that through an act of collective imagination, a family can bring such a small wonder to life. Given's work walks a fine line between the sentimentality marketed by commercial photography and the simplicity of handicraft. In Given's presentation, the carved peanuts seem to have an elevated importance, mimicking the role of storytelling in the perception of events and people within families.

A Vietnam native, Chau and her family came to America as refugees in the '80s. Having learned her own family's history through oral traditions, Chau relates these and other narratives via the use of common objects such as saucers, thread and crayons. Like Given's peanut elves, Chau's carved crayons are cleverly made, but Chau's work seems lost in the downstairs space where it is forced to share space with other gallery wares. The carved crayons and pencils, such as Classic Girl (2009), suffer the most because of their small scale and the crowded surroundings of the gallery. In this environment, it's difficult to focus on anyone work in particular. The ceramics are more successful in this context. Their fusion of the two handcrafts-embroidery and porcelain-is unexpected and draws the viewer in for further inspection. For example, Hand (2008) depicts a delicately gloved hand pinching a red organza thread that breaks the edge. The image appears surprisingly at the bottom of a teacup balancing the interior and exterior of the form with elegant restraint. Chau's embroidered ceramics brings to mind the wit and wisdom of Meret Oppenheim's early surrealist works, with their use of textural devices and feminine symbolism. Assimilate (2008) takes the form of an oval dish with a silhouette of a blank girl partially filled with parallel embroidery stripes. The stripes begin at the top of the figure's head and disappear at the top of the torso. Here the body is seen as a vessel for the assimilation of forms as well as the cultural assimilation Chau so elegantly describes.

-Mary Anna Pomonis

Short Stories: Diem Chau and Wendy Given closed in April at Fifth Floor, Los Angeles.

Mary Anna Pomonis is a freelance writer based in Los Angeles.

Review: "Wolves & Urchins" and "Warlord Sun King: The Genesis of Eco-Baroque"

By Bob Hicks

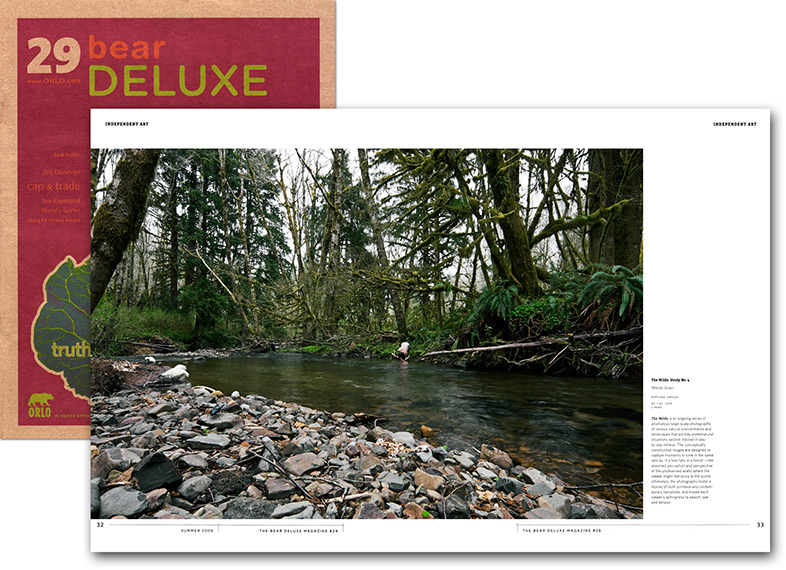

Wendy Given's big glossy photographs are like picture-puzzles of the great Northwestern outdoors, this breeding-ground of existence. It's like looking into nature's womb: the drip, the green, the loam, the rot, the life of the rain forest. Things grow, and grow, and grow. Downed roots gnarl and twist, rocking the cradle of the new. And from some background corner of the gallery the sound of water rushes, burbles, breaks.

<<FULL ARTICLE>>

Sunday, July 18, 2004

Atlanta link comes vividly to the forefront

By Jerry Cullum

FOR THE JOURNAL-CONSTITUTION

John Koegel is the example of home-grown art by an artist raised and trained elsewhere. His baroque, large-scale drawings have retained the same air of mystery, complexity and wit over the years, as shown by a grid of never-before-exhibited 1985 drawings juxtaposed with one from 2004. The other artists here, who range in age from late '20s to late '30s, got their start locally (three at Atlanta College of Art, two at the University of Georgia). All except one then went on to the Northeast or California for graduate school.

Tyler Stallings has gained fame or notoriety as an innovative museum curator, and his little paintings of big-eyed people and animals show the quality of his imagination. Poised somewhere between sci-fi and the kitsch of Margaret Keane, they're disturbing and indisputably serious, mixing and transmuting usually despised genres in the same way that his exhibitions have.

Wendy Given's "Domestic Predators" collages and photography possess a similar willingness to confront cuteness and make it scary. These intelligently arranged critters are totally unthreatening, but you'll never look at doggies or kitties quite the same way again.

Ridley Howard's preparatory drawings for paintings share this general unnerving quality, in part because they render near-cliché scenes (such as a newsworthy figure emerging from a jetliner) in a sparsely composed way that would suggest children's drawings if the faces and proportions weren't so precise.

Douglas Weathersby's photos look both colorful and ominous, since they so clearly feature swept-up dust and debris. But the DVD from which these stills are extracted is an extraordinary piece of visual poetry, creating musical-looking scenes of light and air from the paint scrapings and Sheetrock dust with which the artist works professionally.

After this profusion of emotionally arousing images, the cool abstraction of Kathryn Refi's outlines of driving routes comes as something of a respite. Her grid of linear assemblages in starkly white shadow boxes is also the perfect complement to Koegel's richly filled grid of graphite drawings; we've gone from elusively excessive images in the work of the oldest of the artists in the show to equally elusive conceptual mappings in the work of the youngest. They also happen to be the two who live here, but part of the point of "Home Grown" is the difficulty of separating out the East Coast, Left Coast or Southern strands; it may be home-grown, but it's all art, not "local art."

The verdict: A great survey of a slice of home-grown products.

WEEKEND PREVIEW Friday, Aug. 4, 2000

Private universe lurks beneath cartoon surface

By Jerry Cullum

FOR THE JOURNAL-CONSTITUTION

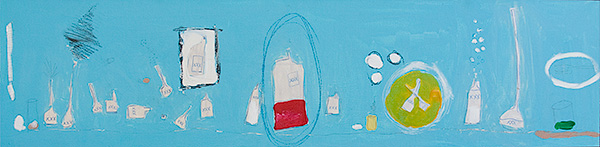

Wendy Given's new paintings, such as "A Spoon Full of Sugar" (2000), are long strips of images that read from left to right.

In any case, Given's acrylic paintings and watercolors with oil pastel are a whole lot more than absolutely dandy cartoons. They're sophisticated works of art that,wear their aw-shucks appearance as a supremely effective disguise.

The new paintings in this show work like cartoons in that they're long strips of images that read from left to right. But the story implied by the sequence is anything but obvious. There are lots of cats, half-full glasses, tableware, maraschino cherries, bottles marked "XXX," eggs frying in a skillet, houses, dogs and rabbits, plus the occasional shark. They all have associative meaning, but not even a Freudian could make glib connections between the elements of Given's private but intensely seductive symbolic universe.

Her technique, though, makes us want to hang around and learn more. The vigor of her style, whether it involves gestural strokes or lines incised into the background paint, gives her most casual looking markings a sense of logic and authority. These compositions feel personal but not arbitrary, not even in the stripped-down world of the works on paper, where only one or two images are juxtaposed.

On the other hand, they remain largely indecipherable. A line of five cherries recurs in two paintings; in one, four cherries are blue and a larger one is red; in the other, four are red and one is blue. Other repetitions, such as rows of glasses with varying amounts of liquid in them, also seem to be shorthand for a complex situation. Given writes that these works satirize absurd personal experiences "while sparing the viewer the gory, boring and tedious details." Since the art-world trend is the presentation of numbing quantities of literal biographical detail in as scatologically confrontational a form as possible, Given's politeness seems to belong to another era.

On the other hand, tales of traumas redered at an aesthetic remove have the capacity to slip past the inner censor and wake us up from within. Though Given's imagery doesn't use familiar Freudian language, it works the way Freud told us that dreams work: It condenses painful things and replaces them with something that is easier to contemplate. And though these paintings are still only promising but exciting beginnings, that process is also one of the things great art has always accomplished.

The verdict: Darkly irresistible; simple, but anything but childlike.

Jerry Cullum is an Atlanta writer and the senior editor of Art Papers, a magazine of contemporary art.

FORTY WINKS FOR THE FOUR-FOOTED

Nancy Solomon Gallery, project room

April-May 1997

Written by Jason A. Forrest

Art Papers, July/August 1997 p.48

One of the primary goals of any artist, no matter how noble, is ultimately self-promotion. Not only is Ms. Given reassigning identity, but also she is resigning the authorship of her very art itself. This concept could lend itself to disastrous consequences, but in this artist's work it points towards larger phenomenon. In many ways this is an attempt to escape. Not only has the media labeled "X-Generation", of which Ms. Given is a member, been saturated with commercials, sales pitches, news friendly murder and other signs of general corruption, but conversely it has been weaned on a bizarre hybrid of children's entertainment (Speed Racer, The Bugaloos and the infinitely bizarre H. R. Puffinstuff). One of the only places of refuge has been the imagination, to which many younger artists are fleeing.

Also, the very notion of resigning authorship is an affront to the ever-increasing star power of the upper echelon of famous artists. Upon walking through any major museum, one is immediately aware of whom they are seeing. The history conjured up between artist intent, and art-writers' theology has bred a thick mythology believed and accepted by the art-viewing public. To lay eyes upon a David Salle painting is to bring to mind innumerable essays concerning the artist's place in the gestalt in art history. What better way to undercut the foundation of the hierarchical systems of art society than to un-become an artist at all? In fact Ms. Given's work is created by creatures not human at all, let alone even in the realm or "rational" thought (ex: Adam the Bubble Gum Man was discovered after being "cut from Ms. Given's hair as a child".) Furthermore the lack of Adult characterization, pushes this concept even further by under cutting the thick clouds of maturity surrounding modernism, post modernism and every other -ism to manifest itself.

Another shock to the system is that this group show of imaginary creatures is presented in a commercial gallery. Initially, one would think that what would be for sale were the objects created by the artists; and these objects are beautiful, most of which are nicely framed. But yes, the artists (as sculptures) are for sale along with their creations. Not only making for savvy installation art as such, but also making a far darker proposal about our shared culture of consumerism and art as commodity. One must not only applaud the effort of the artist but the courage of the gallery to present an art which for even the most informed art buyer, would be seemingly unmarketable.

And finally the obvious reason remains that to resign authorship is, in a way, to play it safe. The act of creation and exhibition is a severely personal act of which demands a great amount of personal security. What better way to disregard prying comments but to disclaim not only the intent of the art works but also the very creation of the objects themselves?

With an installation created from the standpoint of such a bizarre group of creatures, it is entirely too easy to dismiss the work as strictly absurdist. Almost every element in the exhibition displays large reference to a childlike imagination where our friends can be any types of creature—or thing. The drawings and paintings displayed are also childlike in look or implication. But the accumulation of all these various signs points toward unsettling meanings under the various pieces. The "artist" which is an egg, Bronwyn Leighton, displays three paintings of humanoid chickens in conversation, collaged onto which are small photos of airplanes in flight. Which brings about a dialogue concerning the lost nature of chickens as birds, the symbolic loss of flight, if not the loss of religious faith. Ms. Given seems to be trying quite hard to gloss over the pieces with so much absurdity that the actual objects begin to get lost in the larger concept of the characters. But there is meaning in the flat work provided.

In fact, general themes can be applied to the creations of the fictional characters. Most speak of kinship toward friends and family, but a certain strain lurks under the surface. A sense of adolescent confusion develops similar to the feelings one has while growing up where rules are enacted for reasons unknown or personal tragedy strikes with little consolation or explanation. Perhaps exploring the psychological nature of each persona more completely (as well as each individuals personal artistic style) could further heighten Ms. Given's concepts, as well as the enduring effects on the viewer.